Home > CR Interviews

Home > CR Interviews A Short Interview With Eddie Campbell

posted May 7, 2006

A Short Interview With Eddie Campbell

posted May 7, 2006

There's no artist working in comics today whose body of work I admire more than Eddie Campbell's. His books are among a handful that you can read at your lowest point of respect and regard for the medium and after closing the final page come out fighting for any and all things comics (although as he points out, Campbell may no longer join you on the front lines). He is also an underrated figure in industry history aside from his artistic contributions, putting out work in a variety of formats via small press outlets, alternative comics houses, independent publishers, self-publishing, and now the large publishing house First Second. As you'll likely notice here, Campbell has a well-deserved reputation as a fascinating person with whom to converse. If there are any slow parts in the interview to follow you should blame my being intimidated.

The book that gave us the opportunity to talk?

The Fate of An Artist, a formally ambitious and severely attractive work that much like Charles Burns'

Black Hole reads like both a brand new work and a masterful reconsideration of familiar themes. In Campbell's case this includes family dynamics, an artist's attitude towards work, and most provocatively the shortcomings and absurdities of autobiography. It's a fun read, and a thoughtful piece of art. If First Second were for some completely unforseen reason to crash and burn tomorrow,

Fate of the Artist would be the book held up to justify its existence. You should buy it; I guarantee you'll read it more than once.

TOM SPURGEON: You've criticized the ebb and flow of Internet discussion about comics, and in fact in Fate of the Artist

, your anger at some of these conversations is mentioned in humorous fashion. But it's still mentioned. I've always been dying to ask you: what would you like to talk about? Do you think there are things that this ongoing, engaged conversation can accomplish that it hasn't by virtue of topics selected and rhetorical strategies employed. Ideally, what would comics' face in the Internet mirror look like?

EDDIE CAMPBELL: I can't remember what I was beefing about with regard to the internet. I did used to get wound up about stuff but I've got it off my chest already. For various neurotic reasons I closed my

web site a couple of years back, and I made a rule with myself that if I were to drop in on

the Comics Journal site I should make my statement and then get the Hell out of it and don't enter into any discussions or follow ups, as internet discussions tend to follow the rule of diminishing returns. However it was after I'd made that rule that I then got on there and worked out the

"Graphic novelist's manifesto" over several posts in June 2004. That would have to be my most reproduced piece of writing and you can probably still find it in a dozen places on the net. I think the internet is one of those

Marshall McLuhan things. The medium is the message. The fact of the medium itself tells us more than any of the blather that appears on it. However I've been dropping in here and

there over the past few months, trying to be a guerilla blogger. Mostly that means being a guest on the

First Second blog. The secret of the medium is in the wormholes. Writing and reading such pages will have a comprehensive effect on the way our minds work.

I've tried to use this kind of non-linear reading in Fate. Thus you'll get words or objects that seem to glow like little hyperlinks, inviting you to another part of the book. Like "Vigintillion" or "screamer" or "A. Humorist." After a first, linear reading of the book, the reader is tempted, nay compelled, to go back and start reading it in a completely non-linear way, "clicking" backwards and forwards, and in doing so, realizing that they are accruing information at a much faster rate that way. And, you know, long after finishing the book, there are dozens of other little links that i wish i could go back and put in there simply by changing a word or phrase here or there. I'll have to do a George Lucas and fix it up several years from now. Anyway, I guess this was the purpose of having several separate threads of reality going on in the book, so that I could create a complex environment of "links," pages of text full of "wormholes."

SPURGEON: One thing that fascinates me about

SPURGEON: One thing that fascinates me about The Fate of the Artist

is I can't quite gather how

you worked on it. For instance, can you talk a little bit about how you worked on the pages featuring imagery and text -- were you working directly with some sort of typesetting and then working in the imagery?

CAMPBELL: For some time now when I look at comic books all I can see is a straitjacket. The form restricts itself at every turn. For instance, the artist sits before his blank page. If his first picture is a big square one all the way across then he has severely limited his second panel to having to fit in the letterbox space along the bottom. If he divides that in two then that third panel is looking like a sad and defeated cornered animal. That's about all i see when I look at comic books now. Obviously the artist doesn't do it that way; he plans the whole page simultaneously. But it tends to read like he planned it that way, and that's all that counts. And then all our theories about how comics are put together are invariably about time. The duration of a panel's action and the duration between one panel and the next. We haven't added very much to the Eisner-Steranko concept of "sequential art." And if the form is to say something important, rather than just involve itself in the kinetic thrill of drawn characters chasing each other, then we have to think harder.

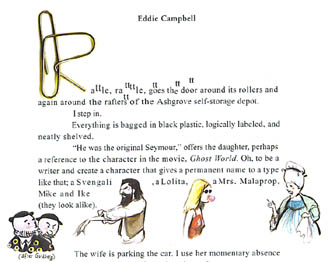

So I've been thinking about typography lately, the art of organizing the appearance of printed matter. I've been looking at recent serious books that have incorporated pictorial matter such as Umberto Eco's

The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, and Jenny Uglow's

The Lunar Men. But these are still typeset books in the traditional manner. I wanted to go further than that and do every letter of the typesetting myself, even though it's not something I've done before. I was aware that there would be incidents that professional typesetters would consider to be technical errors, but I wanted the setting to have something of the feel of my hand lettering, which is to say that it would be governed by the same critical if idiosyncratic eye. It took me far too long to do it of course, but when i was finished I made it clear to the editor that he was to regard the setting as though it were a page of art, and if he americanized any spellings, he was to make sure the spacing was still exactly the same as before. I played around with special effects in the type here and there in order to signal to the reader that this is what was happening. And where I've dropped little painted characters in among the text, I did that as though it was on a tracing paper overlay, and Evans, who usually does the design on my books, he put all the bits and pieces together at the end, cursing all the time about my amateurish typesetting. As long as he didn't like it I knew I was on the right track.

SPURGEON: Now that you've finished the work, can you evaluate, even in broad fashion, some of what you think works and doesn't work about those typset pages, and how they might work? Do you think you've added to the Eisner-Steranko concept? Did any of the results surprise you?

CAMPBELL: The typeset pages work fine, allowing that they are, when all is said and done, just a big joke, but of course i consider myself as being in the joke business and

Fate of the Artist is but a colossally elaborate jest. As for my remark about the prevailing concept of "sequential art," I realize suddenly that I may have come across like Sienkiewicz and McKean used to, when they would proclaim that they were "making up the vocabulary as they went along." You led me unawares into talking about the technical angles, which I usually flippantly avoid. But now that I'm here, I'll press ahead.

Lies demand a higher degree of verisimilitude than does the truth. So that particular domain of comic books which specializes in pulp genre fantasies has evolved a style which has certain attributes. For instance, the thought balloon has become anathema to this style, and the "talking building" has been expunged from its narrative technique. In both these instances, the voice-over is applied. This is a technique borrowed from movies, the immediate model of verisimilitude to the modern writer. And as long as comics are in thrall to cinema, then they have denied themselves access to a vital pictorial language of signs and symbols that is in fact very old. Artists like Ware and Seth, to name but two, have hacked a pathway through the undergrowth back to the source. Let me give you a hypothetical situation. Max Collins was able to write a novelization of

Road to Perdition without much bother, but Seth would find it impossible to write a novelization of

Wimbeldon Green. The latter was completely conceived in this purer pictorial language and to translate it to the less effective one of a text novel would be creating a lot of pointless labor. (I hasten to add that I don't mean this as a put down of the former.)

SPURGEON: In a more general sense, how did you orient yourself to the different forms you used while you wrote? Did you write with those forms in mind -- plan them out, or did you have a "text" at some point and then work on executing that text?

SPURGEON: In a more general sense, how did you orient yourself to the different forms you used while you wrote? Did you write with those forms in mind -- plan them out, or did you have a "text" at some point and then work on executing that text?

CAMPBELL: In the same frame of mind as I just described, I thought if I start in one mode, am I stuck with that all through the book? Can I switch to, say, a Fumetti, (ie photographic) mode? What if I use all the various modes, going from one to the other and back again? what if i put daily and sunday newspaper strips in there? What if I do a "classics illustrated" for one chapter? What if it all starts mixing up and cross referencing? I had a vision of the book I wanted to do in my head, but it was never written out. I just kept adding to it until I had the desired number of pages, but adding to the front, back and middle all at the same time. It certainly didn't come out in a linear manner. And once I decided to do a daily strip, I wanted a whole mock daily section, on yellowed newsprint, and then a mock sunday section, in full color, placed exactly in the center of the book. Every new idea was accompanied by mad giggling at my audacity, followed by days of terror at the thought that that I had bitten off more than I could chew.

SPURGEON: Was Mark Siegel as involved as closely as an editor on this book as he has been with some of the others? If so, what was that relationship like and how did it affect your process?

CAMPBELL: Mark is a good editor. There's one place in the book where he pushed me further than I felt inclined to go and It was for the best. Having created the idea of a murder mystery I presumed my readers would accept that it was just a gag and not need any kind of closure. Obviously the author has not really been bumped off since he's still here drawing the book. But Mark felt that the terms in which I had set it up, a mock private eye first person narration, demanded a resolution. So I cooked one up, and it's kind of an in-joke for librarians, and it got quoted in the

Booklist review. Strangely though, one of my regular readers here, before I told him that, thought it didn't sound like something Campbell would do. So there you go. I do tend to dread the editorial process though. I'm finishing

The Black Diamond Agency soon, and I'm just hoping it makes sense and I'm not tied up for another month rethinking passages. Still, it's got to be done. Perfectionism. In the old days when I was putting my stuff out in the monthly

Bacchus I could judge responses as I went along, which made self-editing much easier when it came time to collect the material.

SPURGEON: More specific again: I'm impressed with the sections featuring photography, and was intrigued by seeing Hayley listed as not only the subject of those photographs but as the photographer. Can you describe a bit how those sections came together? Was there any direction on your part?

SPURGEON: More specific again: I'm impressed with the sections featuring photography, and was intrigued by seeing Hayley listed as not only the subject of those photographs but as the photographer. Can you describe a bit how those sections came together? Was there any direction on your part?

CAMPBELL: The "plot" idea of the book is that the author is missing and those who knew him are being interviewed about his disappearance. So it occurred to me, what if I do this part as a photographed interview? I don't think Hayley was crazy about the idea at first, but I said brush your hair, put on your make up and we'll sit at the cafe and I'll take a clip of 24 pictures. Of course, she started getting critical and we had to erase a bunch and reshoot that number, etc. etc. The challenge was to make it look very natural, with no overt gesticulating like you would normally expect in a photo-comic, and to keep it interesting for over 20 pictures. I had to reject a few for one reason or another and then found I therefore had to double-use some of the ones that were left, reversing, inverting, moving closer, because if I'd gone back to shoot some more it would have been too difficult to make it look like the same session. If I ever do it again I'll be better prepared. But as I said, I really was making things up as I went along. Late in the project it occurred to me that she was starting with an empty glass of beer and ending with a full one. So I tried to adjust the beer in photoshop.

The photo Hayley took was the author photo on the end flap, which is a neat joke because in a way it's the final panel of the story. When I had the idea for that we all just tumbled out the front door and took a bunch and later picked the best one. And having got the leash on Monty I had to actually take him for a walk. But anyway, she's been around art for long enough to know how to frame a picture, so I had no worries there.

SPURGEON: Seeing you mention the idea of the missing author as a

SPURGEON: Seeing you mention the idea of the missing author as a plot

formulation startled me because I assumed that the plot followed the thematic idea, that you'd remove the author from the various parts of the book as a kind of ongoing critique of self-representation in your (and others') comics. Whether it's expressed in plot and/or theme, can you talk about what interested you in that subject matter at this time? Because there are multiple avenues through which you explore that: the "actor" playing you, the authorial voice which is someone else entirely, the comic strips, your own appearance as an actor in an adaptation, and so on.

CAMPBELL: It really is a postmodernist soup, isn't it? It came together in bits and pieces. I wanted to recreate these historical situations, like the first one involving Mozart, but it was essential that they be authentic. Authenticity is the all important factor in my work. The problem was that I had no visual reference for Johann Eckard, and it may well be that none exists. I always try to avoid the reconstructive craft of the illustrator. I want my pictures to never look "illustrated." The quality I seek could be described as a compelling immediacy. So I thought what if I pretend it's being filmed in modern times and then I can cast actors in the roles and nobody can say it's inauthentic. Then I noticed that the 18th century topographical artist Karl Schultz seemed to have had this little imaginary cast of characters that he employed to people his prints. They were very human and humorous prints even though the purpose was to show a location, or a building.

So I figured, I'll do that too and have a little cast of actors, and then I thought I could even have one of them playing me, and I could disappear from the book altogether. This tied in nicely with the fact that I had made an abortive attempt to leave home one day. I almost had the spotted handkerchief tied to a stick. It was that sentimental. I didn't get very far before I thought, "Ya great big eejit! Get back and finish yer work." Then there's the adaptation. That was an idea that would have been in the

History of Humor. Now I cast myself in it and it made great wrap up to the whole thing. The other thing you mention is the authorial voice of the private detective, who is never named. Originally I was going to make that Alec Macgarry, but it just seemed to be adding too much confusion to what was going to be a generally marketed book. What all of this means I leave to somebody else to figure out. I got my brain in enough knots just creating it.

SPURGEON: The last story is fascinating because there's a lot of ambiguity as to how the reader should take it. The line "To once more enjoy the apples of life instead of squeezing them to a pulp for a few drops of cider to make the public feel funny" could be read as a severe indictment, and it is the last sustained story in the book, but at the same time, those words aren't exactly yours and you're speaking throughout the book in terms of fate and inevitiablities rather than descriptives and prescriptives. How do you feel about the self-critical aspect to the book? Does it reflect a similar process in your own life?

SPURGEON: The last story is fascinating because there's a lot of ambiguity as to how the reader should take it. The line "To once more enjoy the apples of life instead of squeezing them to a pulp for a few drops of cider to make the public feel funny" could be read as a severe indictment, and it is the last sustained story in the book, but at the same time, those words aren't exactly yours and you're speaking throughout the book in terms of fate and inevitiablities rather than descriptives and prescriptives. How do you feel about the self-critical aspect to the book? Does it reflect a similar process in your own life?

CAMPBELL: I gave the text of the O.Henry story "Confessions of a Humorist" to one or two people to read and they agreed that it really was me in that story. It's about using your nearest and dearest as the subjects of your published humor. So casting myself in it was exactly the right thing to do. And everybody talks about O. Henry as the master of the twist ending, but his prose just drips with juice. It really is lovely. That story has always brought tears of joy to my eyes. I used his words exactly as he wrote them and added none of my own, though I did trim the piece a little. It's another "mode" of comics, to refer back to what I was saying earlier. Illustrating an existing prose or poetry text in continuous running imagery. I avoid the word "adaptation" here, unless the text has been altered in some way or its meaning changed or "adapted" to a new situation. It's just good old fashioned "illustration" (and I'm using that word with a somewhat different inflection from my earlier use of it in this interview).

This is what my

Disease of Language book is, illustrations of Alan Moore's magical text works. I reject the word "adaptation" for this. (The movie

From Hell is correctly described as an adaptation.) Anyway, that came out in January from Knockabout. And talking about "modes" again, I wanted to construct my book using all the modes, and in thinking about this, it wasn't important to me that all these approaches should be "comics" in the McCloudian definition of the term, which you know I have always rejected anyway. In fact there's one page where I've shown an illustration under the text, and it simply illustrates the words exactly, and under the illustration I've repeated the words again. Twofold redundancy. Put that in yer pipe and smoke it.

I think through the graphic novel the concept of comics will get absorbed into a bigger idea of the illustrated book. Text and illustration got separated at the beginning of printing, hundreds of years ago. Computers continue to bring the elements back closer together, and I think there are interesting times ahead.

SPURGEON: Can I get your impression of the present in an industry/publishing sense? You're working with an exciting new publisher, but there are still distributors going under and if I've heard correctly you're having some problems keeping From Hell

in print. It seems like the old problems never go away. What is your sense of this moment in comics?

CAMPBELL: Staying upright in this game requires supernormal survival skills. The printer I used through my whole self publishing period went down over the last few months. I guess that puts me just ahead of events, in that I got out early enough. But I also handed

From Hell to Top Shelf and they were still using Preney Print for that book and got stung. In the meantime I've been making a digital version of the book, which will make it easier to take it to another printer. Thus, so far with

From Hell I've suffered Publishers (Spiderbaby, Tundra, Kitchen) , Distributors (LPC) and now a printer, all going bankrupt. Working with First Second will at least shield me from all those concerns. This publisher is an imprint of Holt in New York, one the half dozen biggest book publishers in the States. So right now I'm just pleased as Punch seeing how neat

Fate of the Artist looks. It really has the highest production values I've ever had on a book. And with their ability to get it into the larger bookstore market I feel that I'm batting in a bigger league.

That's important to me now.

SPURGEON: I don't want to diminish Fate of the Artist

by reducing it to your lifetime journey a to b, because I think there are a lot of fascinating threads running through it, but was your outlook changed in the doing of this volume. And if so, in what way?

CAMPBELL: Doing that book has moved me into the future faster than i was going naturally, one second at a time. I feel that I've jumped ahead some distance. When I walk into comics shops these days i feel that I'm looking at the past. The shelves of new comics are just a big greasy surface, and my eyes slide around all over it, completely unable and disinclined to fasten upon any detail. I really have come to think of all that as a different medium from the one I'd like to be working in. As different as the newspaper strips are different from the comic books, a subject which you've been addressing lately. In fact my ideas about this have changed since the

Comics Journal interview which was taped last september. I've come to feel now that I would rather not be filed with the "graphic novels" because those shelves in Borders depress the hell out of me. Put me in "authors -- fiction" under C. I'm tired of being a spokesman for the idea of the graphic novel. That doesn't work for me any more.

SPURGEON: Can you talk about your next work for First Second and how you see your next few projects coming to fruition? I find it interesting that you're working some pieces in there like the Batman, out of what seems to be a frank and honest exploration of art that you like.

CAMPBELL: Well, of course i have to make a living, and not everything i do is necessarily something I want on my permanent bookshelf, or that I can stand up against the artistic principles you find me spouting about in interviews like this. I'll happily write a Batman story now and then or whatever, and I'll enjoy it too. Usually I do anything I get requests for if i can fit it into my schedule and it's not a pain in the arse. I've got a two-page Harvey Pekar script in the pipeline. I should align myself with Harvey at least once in my career.

In January I had a big book come out which is one of my important works,

A Disease of Language, combining the magic pieces i did with Alan Moore and the big interview with him from my

Egomania magazine.

Disease is published by Knocakabout, who handled the British edition of

From Hell. Those magic works,

The Birth Caul and

Snakes and Ladders are where I started to get away from the linear narrative. They opened up all kinds of new artistic possibilities for me and are an important precursor to

Fate of the Artist so it's good to have them in a bookshelf format at last and at this time. I also think they are the best things Alan has ever written. They are the real McCoy. They pull no punches and take no prisoners. They are the diluted essence of his thinking.

Right now I'm working on

The Black Diamond Agency, which is a work for hire gig that came my way. It''s coming out from First Second and will be 128 pages. I'm on page 103, so the end is in sight. It's based on a Hollywood screenplay and they've given me a free hand in adapting it. Hollywood buggered around with my book so now i get to do it to one of theirs. Obviously it's a completely different sort of work from the

Fate of the Artist, but then so was

From Hell. Can't really talk too much about the details yet as I don't know whether they'll go for all the Campbellian stuff I'm throwing into the mix.

Beyond that, my ideal development is that

Fate will be so successful that I'll get the chance to do another "me" book, but my fear is that I've put so much into

Fate that there's nothing left in the tank.

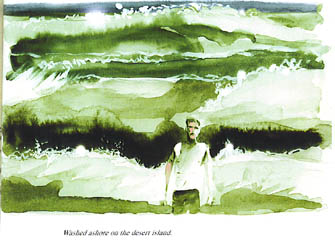

SPURGEON: One last thing -- there are a lot of really fascinating color pieces in

SPURGEON: One last thing -- there are a lot of really fascinating color pieces in Fate of the Artist

, the one that I remember specifically is the image of the artist washed up on shore somewhere, this wall of green behind a figure kind of frozen against it. Can you talk a bit about your approach to color in this book? It looks like there's a lot of single-color-dominant and even partially colored images. I thought it was very striking.

CAMPBELL: That has an interesting genesis. the fact is that I had done around thirty of the pages in grey half tones. When I got the invite to do the book in color I was hesitant at first. I considered adding color digitally, but the page you mention is the only place where I did it that way. For the rest I went in and added color highlights or washes over the grays. That induced an interesting note of restraint in the pictures that would have been difficult to achieve going straight in with a loaded palette. In other places in the book I contrasted that restraint against bold abandon, such as on the page where I'm sticking out of god's ear.

And I've deliberately ended the interview on that odd note. Have a good day.

*****

The Fate of the Artist is on sale now from publisher

First Second Books. Its ISBN is 1596431334, and the price is $15.95.